Upon the recent release of the Netflix-distributed retelling of Daphne du Maurier’s celebrated 1938 gothic novel, Rebecca (adapted for the screen first in 1940 by Alfred Hitchcock, and resurrected this time around by Essex-born filmmaker, Ben Wheatley), and with a slew of other Hollywood remakes scheduled to follow suit later on in the year – including (among others) The Secret Garden, West Side Story and Dune, an age-old debate has once again been reignited amongst film critics and cinephiles the world over:

Is it ever ok to remake a classic, or should they be kept entirely out of bounds?

At loggerheads with one another on the subject are two warring parties: the loyalists and revisionists. The nostalgic loyalists stand firm to the belief that classics are called such for a reason…and their unique legacies should thus be protected and preserved as if they were world heritage sites. The revisionists on the other hand, offer an opposing view: so long as the remake is respectful to its original source material, reimagining and refashioning these classics means that it reaches a whole new generation, who might not have ever bothered (nor cared) to dig up that black and white version anyway.

Whichever end of the debate that you may reside, one suspects that both sides will be sparring it out for generations to come. But, for however many Hollywood remakes that were (and continue to be) a car-crash disaster, tantamount to cinematic blasphemy, believe-it-or-not there are a small minority that actually take the leap (and dare I say it?) stick the landing. To go further still, one might say that there are a handful that hold their own just fine, and stand alone as exceptional works of art.

One such example is the 1951 Columbia Pictures remake of Fritz Lang’s German masterpiece, M.

Justifiably so, trying to convince anyone that an Americanised version of such a groundbreaking picture was a good idea turned out to be no walk in the park. Add to the equation too a spate of political vilification and controversy and it’s surprising that this remake even made it into theatres at all.

When Fritz Lang first heard of producer Seymour Nebenzal’s intention to re-do his seminal 1931 crime thriller for an American audience, he was positively mortified. Consistently regarded by critics as one of the greatest films of all time – and considered by Lang himself to be the magnum opus of his impressive catalogue, he found it simply outrageous that Nebenzal would have even hinted at such an idea.

In his defence, Seymour Nebenzal – the 2nd out of three subsequent generations of well-respected film producers in the family, was arguably more authorised to make this proposition than anyone. He’d already worked closely with Lang in Berlin on the original film, producing M under the umbrella of Nero Films – the acclaimed German production company that had been co-established by his father, Heinrich at the height of the famed Weimar Era back in 1925.

If that wasn’t enough reason, Nebenzal had already acquired the rights to the film too, shortly before Lang (along with many other notable European filmmakers) had emigrated to the USA after the looming threat of Fascism back home.

But despite Seymour Nebenzal’s well-connected network of already established filmmakers – such as Edgar G. Ulmer, Robert Siodmak (Nebenzal’s first cousin), Douglas Sirk and Billy Wilder, he would run into difficulty enlisting them time and time again whenever he happened to mention his intent in producing an Americanised remake of an already acclaimed classic.

Early on, German émigré, Douglas Sirk had initially warmed to the possibility of coming on board as the film’s director, provided the script would be an entirely new and original story based around the plight of a serial-killer. But Seymour Nebenzal was understandably wary…being that the watchdogs over at the Production Code Administration had only given him the green light to remake M because it had already been a surefire hit. Nebenzal knew well-and-clear that the film would be shelved by Hollywood censors if he didn’t adhere to their demands, so in the end Douglas Sirk would pass on the idea too.

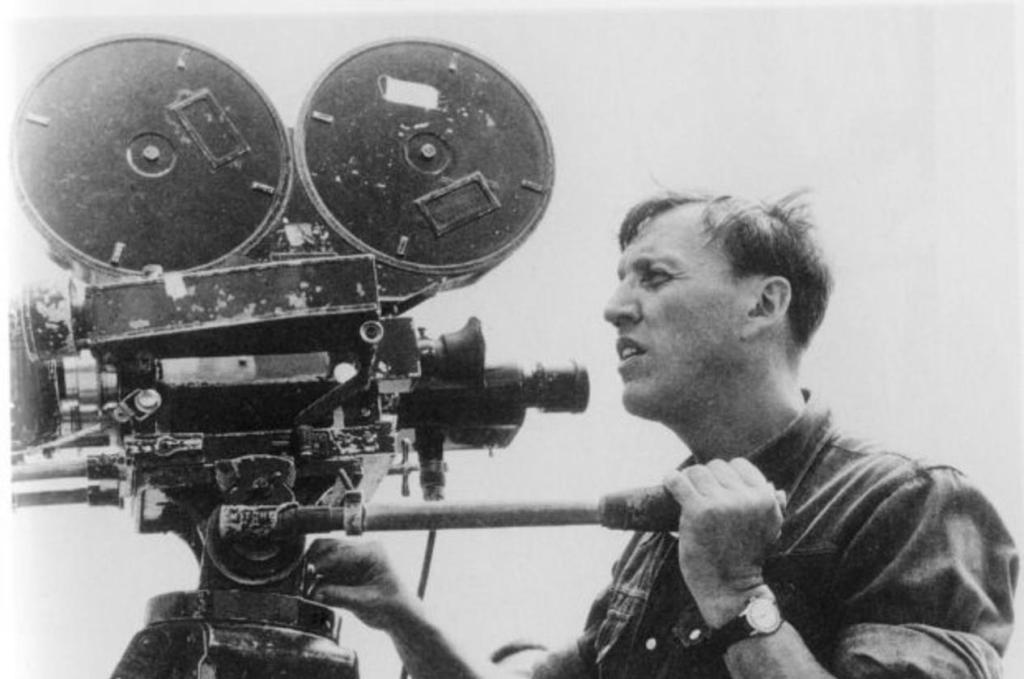

Finally, Nebenzal hired a young American filmmaker by the name of Joseph Losey to direct the Hollywood version of M; setting the updated picture against the bustling backdrop of downtown Los Angeles – as opposed to Berlin, where the original had been filmed some 20 years prior.

Losey had recently wrapped up production on his 2nd feature for Paramount Pictures: The Lawless – a prime example of what later became known as film gris: a type of noir that came out specifically between 1947-1951, portraying a cynic’s disillusioned outlook on capitalist America.

Both producer and director quickly assembled an impressive catalogue of cast and crew – including Nebenzal’s son Harold as assistant producer, Hungarian-American cinematographer Ernest Lazslo, and a young Rhode Island filmmaker that was cutting his teeth as assistant director, the great Robert Aldrich (Lazslo and Aldrich would go on to work together again on a string of incredible films like Vera Cruz, The Big Knife and Kiss Me Deadly).

Signing on too were a number of versatile actors in supporting roles that had honed their craft first on the stage, like Luther Adler, Howard Da Silva, Raymond Burr and Martin Gabel (a former member of Orson Welles’ famed Mercury Theatre Troupe). This time around, the lead role of the killer who epitomised evil would go to American actor David Wayne; a risky choice, considering Wayne had up until this point typically played supporting roles in mostly light-hearted romantic comedies and musicals.

Having stepped into a role that had: a) already been made iconic by one of the greatest actors of his era, Peter Lorre, and: b) was one of cinema’s most detested and widely controversial characters, must have been both daunting and overwhelming. In any event, Wayne seems to have embraced this with an intrepid enthusiasm, playing nefarious child killer Martin W. Harrow (the killer in the original film was called Hans Beckert), and reimagining the villain within the context of postwar America.

Wayne must have realised early on that it would be near impossible to equal the performance of his onscreen predecessor; and so he makes no attempt in replicating Lorre’s signature expressions or mannerisms. Instead, he delves into the mind of the mentally disturbed predator… peeling back the layers of psychosis on screen with a sadistic pleasure – as if he were plucking the legs from a helpless insect. He appears equally tormented by his sick thoughts as we are repulsed in watching them…luring the innocent children like the Pied Piper of Hamelin with his flute.

“Ordinarily you look for a dame or a bankbook, get a victim with known enemies – what do we got? Some missing shoes. What’re we looking for? A man with a twisted mind. Could be anybody…”

Inspector Carney (played by Howard Da Silva)

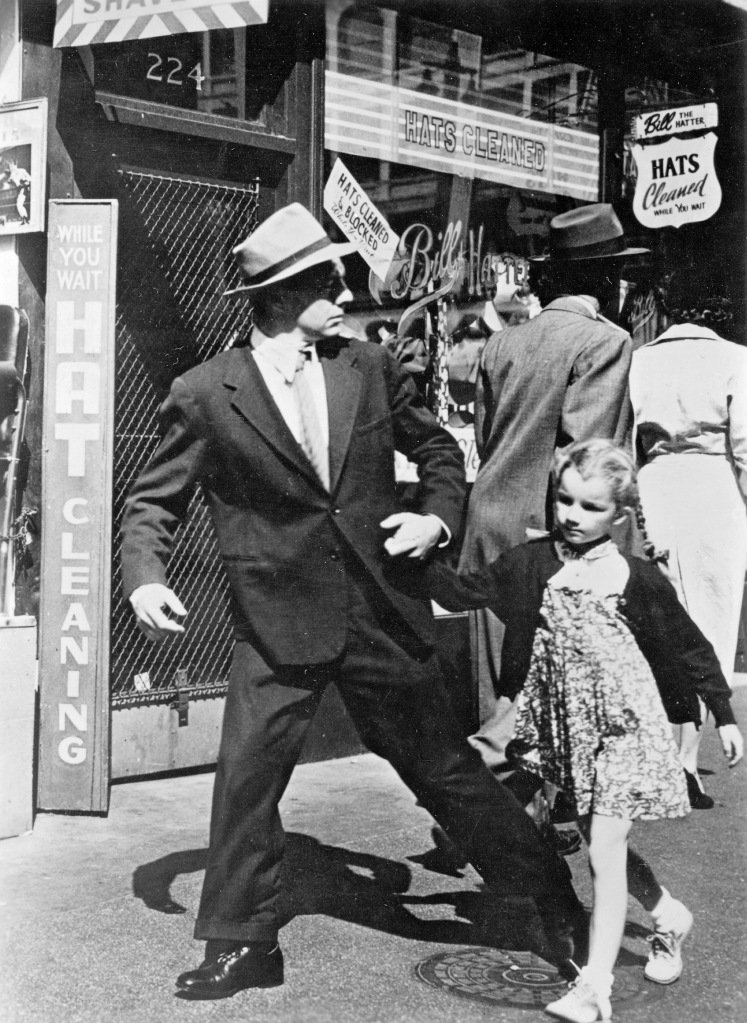

True to Fritz Lang’s source material from which it is based, the 1951 version rarely veers too far off course from its original plot: the kidnapped girl is still called Elsie, the killer is still branded with a capital ‘M’ on his shoulder, both the homicide squad and the mob still put out their own dragnet in order to apprehend the killer. And yet, there is something about the story being plucked from pre-war Berlin, and planted in the streets of Los Angeles (somewhere between the end of WWII and the Cold War), that gives the social commentary in this film a second life.

This is credit to the collaborative talent of both cast and crew: the sumptuous cinematography and location shooting of DOP Ernest Lazslo, the way in which editor Edward Mann propels the story forward through juxtaposed imagery, the climatic musical score composed by noir staple, Michel Michelet, or the wonderful ensemble of supporting cast members that earned their stripes first on the stage.

Perhaps another key factor that makes the Hollywood version of M suddenly seem relevant again are the brutal scenes of mob justice – as the public, the police and the criminal underworld descend into a feverish madness, overcome in the end with the intoxicating scent of vengeance, and the enforcement of a hard justice that can only be decided outside of the courtroom, on the cold concrete ramp of a city parking lot.

Looking back at it now, director Joseph Losey may well have related to the witch hunt portrayed in M more than most. He’d already been watched closely by the HUACC for some time by now – due to his alleged affiliation with various outspoken industry figures and filmmakers accused of sympathising with the political left, including several vilified individuals who would later be condemned in the Hollywood Ten – like screenwriters, Ring Lardner, or Dalton Trumbo.

The subsequent witch hunts that were to follow in the late 1940’s-1950’s in the McCarthyism era bore a frightfully similar choreography to the judicial bedlam witnessed in M… with those accused of communist sympathies dragged before the federal courts and forced to ‘name names’.

Not surprisingly, the remake of M was boycotted at screenings in several major American cities because of Losey’s alleged ties with Communism; and it was pulled altogether from theatres in Ohio due to its controversial subject matter, which incensed many powerful individuals of the conservative right. As a result, many including Joseph Losey himself, dialogue writer Waldo Salt, and actor Howard Da Silva (who ironically plays lawman Inspector Carney) were blacklisted from ever working in the industry again shortly after the film was released.

Losey, already an accomplished and well-respected Hollywood director, was forced to abandon post-production in the cutting-room prematurely for his next film, The Big Night later that year, as the HUACC tried to serve him with a subpoena to appear in court, accused as a traitor to his country. Losey left for Europe shortly after with his then wife, Louise – which of course resulted in his work in Britain with playwright Harold Pinter, and a string of acclaimed films like The Criminal (1960), The Servant (1963) and Accident (1967).

“So, after a month of finding that there was no possible way in which I could make a living in this country, I left. I didn’t come back for twelve years…I didn’t stay away for reasons of fear, it was just that I didn’t have any money. I didn’t have any work”.

Joseph Losey

Admittedly, aside from leaving a bitter taste in one’s mouth, many film remakes are not worthy of appraisal – let alone any accolades (the remakes of Scarface, The Fly, Nosferatu and Hitchcock’s remake of his own film The Man That Knew Too Much are all worthy exceptions). But it’s a shame to see that some, like the Hollywood remake of M, have been forgotten not because they weren’t particularly notable bodies of work in their own right, but instead because of politics, censorship and controversy.

If there is anything we can learn from this, it is that these remakes do indeed make for interesting comparative analysis; helping us to better comprehend why these original classics continue to be so groundbreaking and influential for generations of filmmakers the world over.

It’s worth mentioning that in the end Fritz Lang warmed to the Hollywood remake of his magnum opus film; later remarking that the 1951 version earned him the best reviews of his career.

One comment