Take a second to close your eyes and visualise the perennial filmmaker: sitting attentively and ever-astute, calling the action as they see it from the viewpoint of their director’s chair.

Now, with that image in mind, throw away any preconceptions of a short and tenuously fragile figure, bespectacled or balding, living out their sheltered lives through the distorted vision of the camera lens.

What you would be left with would be the very uncommon stature and 1.88 metre frame of the renaissance man.

As far as stereotypes go, the image of John Huston was atypical to the Hollywood mould. His was a voluminous reputation that bore no resemblance to any of his predecessors. A nonconformist and maverick, his cinema was as colourful as the path he etched out in everyday life. An adept screenwriter, director and actor, his films were often forged from personal exuberance and worldliness.

At various stages in his life he had dabbled in boxing, journalism, portrait painting, poetry, documentaries, and as a cavalryman.

The Hemingway of Hollywood was a visual filmmaker, who used his experience as an artist to sketch scenes and meticulously frame shots on paper before rolling the camera.

A voracious writer; he began his career crafting scripts for the likes of William Wyler, Raoul Walsh and Howard Hawks in his mid-twenties before going on to direct 37 films, receive 15 Oscar nominations and several lifetime achievement awards. He is also the only filmmaker to direct both his father Walter Huston and daughter Anjelica Huston in separate films that have each won them Academy Awards.

Through an illustrious career in cinema that spanned almost half a century, the renaissance man was anything but safe. Breaking down the master’s oeuvre into a chronological triptych, we can gain a better understanding into the artistry of John Huston.

The early decades are most significant for his groundbreaking work with such noir films as The Maltese Falcon (1941), Key Largo (1948) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950). Through these films Huston would introduce us to actors that would become staples in his films like Humphrey Bogart, Peter Lorre, Sam Jaffe and Marilyn Monroe.

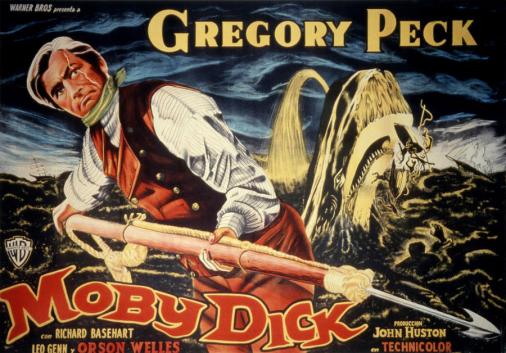

Not to be outdone were his epic quest dramas like The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre (1948), The African Queen (1951) and Moby Dick (1956). Most of the time upon the backdrop of exotic locations or vast landscapes the director would introduce us to rogue characters, social outcasts and unlikely heroes.

Through the 50’s and 60’s John Huston continued to release bold films and social satires like Beat The Devil (1953), The Misfits (1960) and his retelling of the Tennessee Williams play Night Of The Iguana (1964). Often knee deep in drama and dealing candidly with social issues and taboos, Huston’s films still managed this with tongue-in-cheek humour and dry wit.

The tail-end of Huston’s career was no less inspirational; perhaps most notable for the humanistic dramas centred around protagonists who were anything but heroes. Such films as Fat City (1972), Wise Blood (1979), Under The Volcano (1984), Prizzi’s Honor (1985) and The Dead (1987) successfully exposed the vulnerabilities and insecurities of the common man.

When discussing filmmaking, John Huston once said:

‘The directing of a picture involves coming out of your individual loneliness and taking a controlling part in putting together a small world’.

Those many contributions to cinema, each a small world in their own right, have enjoyed something of a revived renaissance with future filmmakers and cinema enthusiasts over the years.