‘I’m going to give the people what they want. Sensation, horror, shock. Send them out into the streets to tell their friends how wonderful it is to be scared to death…’

– Crane Wilbur

In it’s earlier stages, the postwar outlook amongst most in Hollywood was seemingly upbeat, and there was a genuine optimism within the studios that the decade to follow would prove more promising yet. The three years leading up to 1945 had been some of the industry’s most profitable to date, and by 1946 almost two-thirds of Americans were now going to the cinema at least once weekly.

But, as the weary tides of serving war veterans eventually returned home, they brought with them a new melancholic outlook upon the foreseeable future of the country. Political paranoia and economic instability was leading the nation into a palpable state of panic over the threat of Communism. And with the establishment of the House Un-American Activities Committee came the political witch hunts under the era of McCarthyism, the likes of which saw the creative blacklisting of over 400 of the industry’s actors, writers, directors and producers by the early 1950’s.

These idealogical adversities were further exacerbated by the studio’s own rapidly mounting financial problems. A key factor to this was the wider availability of television, which resulted in a serious plummet of ticket sales at the box office. Payrolls and budgets were slashed as a result, forcing filmmakers to scale back their ideas and think more economically than their frivolous spending predecessors.

Whilst these two consequential factors were inadvertently contributing to a gradual shift in a new style of cinema, it was society’s changing attitudes that was to shape the industry’s subject matter and plot lines for the film industry’s scripts. Lavish tales of high society were suddenly being replaced by pessimistic stories of corruption, crime, murder and blackmail. The roaring musicals of yesteryear were now being overlooked for darker-themed plots, centering on disenfranchisement, alienation and fatalism. Consequently, the blueprints for what would become known as noir were by no means predetermined, but rather the creative bi-product of the changing fabric of society at the time.

The string of postwar crime films that were either written or directed by Crane Wilbur are particularly significant for their gritty stories, mostly inspired by real life events and newspaper headlines that were circulating at the time. Wilbur often opted for real prison wardens, police officers, ex-goons or actual eyewitnesses over actors to give his films an added authenticity.

He shot the majority of these films on location in prisons, precincts or at crime scenes. Though much of it could well be perceived as overly patriotic or pro-American, Wilbur also used cinema to illustrate various courthouse inequities during his time, as well as highlighting the many issues of reforming the prison population back into society.

His work during this period with such cinematographers as Bert Glennon and John Alton, and directors like Anthony Mann and Phil Karlson have given much of these films the dark visual style and raw subject matter akin to the movement of cinema that would later come to be known as noir.

With a background that consisted primarily of theatre and vaudeville acts, Crane Wilbur already had at least 12 years of acting under his belt before his career even began in silent films. From his first on screen appearance in 1910 with The Girl From Arizona, Wilbur went on to star in 16 other films within the next 3 years.

He returned to the stage during the 1920‘s; reworking plays like The Bat and The Monster, the latter of which he also starred in. Much of his work during this period was a success, and by 1934 he had already produced 7 plays on Broadway alone.

Wilbur also received acclaim for a handful of radio programs he directed and produced, including Big Town, which aired for 15 seasons and later spawned screen adaptations and comic book lines.

His re-entry into Hollywood came in 1929, and he appeared onscreen as an actor up until 1945. In his long career that encompassed silent films to sound, he wrote or directed at least 67 films.

‘The movies pay me better but I’d rather have my audience in front of me personally…’

-Crane Wilbur

Crane’s infatuation with crime was evident in the screenplays he wrote for such Warner Brothers films as Alcatraz Island (1937), Crime School (1938), Girls on Probation (1938) and Blackwell’s Island (1938). Whilst films that he directed, like Tomorrow’s Children (1934) or The Patient in Room 18 (1938) dealt candidly with delicate moral and social issues at the time, as well as exposing legislative flaws and erroneous decisions made within the courts.

Arguably however, the films produced in the next decade following the war is when Crane Wilbur really began to take his stride, with an important string of crime films produced by multiple studios, including Eagle-Lion Films, Universal Pictures, Warner Brothers and Allied Artists. Drawing inspiration directly from the news stands, these films incorporated stock footage and newsreel style narration to give the crime film more grit and street credibility. It’s suspects or witnesses addressed the camera directly whilst being cross-examined and interrogated, and it’s plots meticulously followed the procedural steps of those fighting to uphold the law, as well as those seeking to break or evade it.

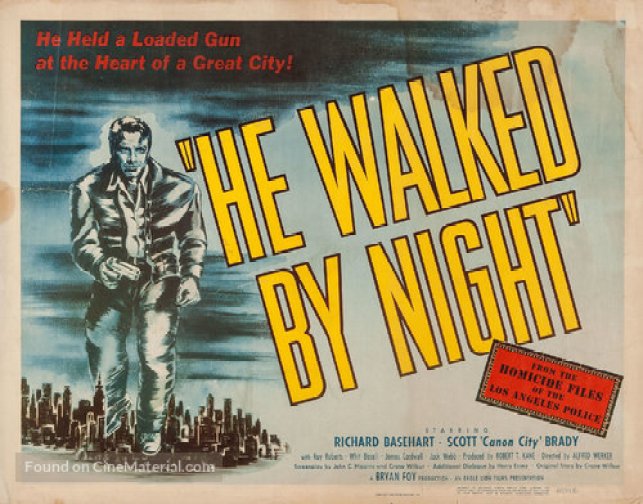

Wilbur released three of these films (He Walked By Night, Canon City, The Amazing Mr. X) in 1948 with the British studio Eagle-Lion Films, adhering to tight budgets and quick turnarounds, and working closely with the great cinematographer John Alton on each of them. Accompanied with the darker subject matter of Wilbur’s scripts, Alton draped the sets in shadows or used available light exclusively when shooting on location, providing a gloomy arena in which Wilbur’s amoral crooks and dogged lawmen could duke it out.

In He Walked By Night, an ingenious recluse (played to devilish perfection by Richard Basehart) who has made a business out of petty crime brings an investigations team on his tail after a bungled robbery attempt ends in the shooting of a police officer. The film was co-scripted by John C. Higgins, who also wrote the screenplays for Anthony Mann’s crime films T-Men and Raw Deal, which were both produced by Eagle-Lion around the same time (see the Privilege of Legends article Mann Synonymous with Noir for more information).

Incidentally, both were also shot by John Alton, and Anthony Mann replaced director Alfred L. Werker on set halfway through filming. The film’s climatic end chase scene through the city’s urban sewer system reminds one instantly of another more famous climax in Carol Reed’s The Third Man, which was released the year after.

‘Starting in high gear, the film increases in momentum until the cumulative tension explodes in a powerful crime-doesn’t-pay climax…’

(Variety Magazine)

Based on an actual prison break that took place the year prior, Canon City was shot in 19 days, almost entirely in and around the actual location of Canon City penitentiary in Colorado. Establishing the story with Wilbur’s signature newsreel style introduction, we are then formally introduced to detectives, wardens and inmates before moving into the swift-paced drama of this escape film with a twist.

In John Alton’s book Painting With Light, Todd McCarthy briefly touches on the fact that the cinematographer took no extra lighting equipment with him into the prison, utilising only the existing light fixtures within the building.

Although more a tale of a psychic fraudster than Wilbur’s more conventional crime film, The Amazing Mr. X (released in some countries under the title The Spiritualist) is particularly notable for it’s controversial shadowy look that perhaps best exemplifies film noir. Crane Wilbur’s original story was initially bought by ‘B’ films studio Producers Releasing Corporation with Wilbur himself planned to direct.

Eventually the film was acquired by Eagle-Lion, with Bernard Vorhaus making the picture under a two-release deal. Despite the original script being reworked in the end by screenwriter Ian McLellan Hunter (Hunter is most remembered for fronting for the blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo as the credited writer for Roman Holiday), the pulp of The Amazing Mr. X still bares much of Crane Wilbur’s distinctive penmanship, and even John Alton himself has stated that his camerawork in this film is indeed some of his finest work.

‘We were shooting day for night, and I said to John, suppose we shoot right into the sun and get some glare, and he said “Why Not”?’

(Director Bernard Vorhaus on ‘The Amazing Mr. X’)

The following two years Crane Wilbur didn’t slow his momentum, nor did he attempt in any way to tone down or sweeten the potency of his crime films. Under a temporary deal with Universal Pictures, he wrote and directed The Story of Molly X in 1949, and Outside the Wall a year after. Wilbur returned to the familiar territory of the prison system to establish both stories, with each film anchored around their convicted protagonists as they struggled to reform from the consequences of their misdeeds.

If anything can be said of the crime films of Crane Wilbur then he certainly demonstrated on more than one occasion that the violation of the law was not always exclusive to men. His early scripts for Crime School (1938) and Hell’s Kitchen (1939) were centred around a group of juvenile delinquents (played by The Dead End Kids in both Warner Brothers releases), whilst The Story of Molly X, like Girls on Probation in 1938, and his very last film, House of Women in 1962, were all primarily female protagonists.

‘I like to try new methods. I believe in using very little gesture, in depending almost entirely upon expression and strong, slow, tense action…’

-Crane Wilbur

In the earlier half of the decade of the 1950’s, Crane Wilbur got back behind the typewriter to craft his tales of crime, writing screenplays for Warner Brothers once again with I Was a Communist for the FBI in 1951, and Crime Wave in 1954, as well as directing Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison in 1951.

Crime Wave is the standout champion here, with the scripts for both films adapted by Wilbur from short stories which originally appeared in separate editions of The Saturday Evening Post. Sterling Hayden plays the hard-nosed detective on the trail of a gang of dangerous fugitives, in a cat and mouse hunt through the seedy backstreets and bars of Chinatown and downtown Los Angeles.

Much of the film was shot on location by cinematographer Bert Glennon, who also worked with the great John Ford on several of his major westerns, including Stagecoach (1939), Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) and Rio Grande (1950), and had also just shot the film adaptation of Crane Wilbur’s script for the horror House of Wax a year earlier.

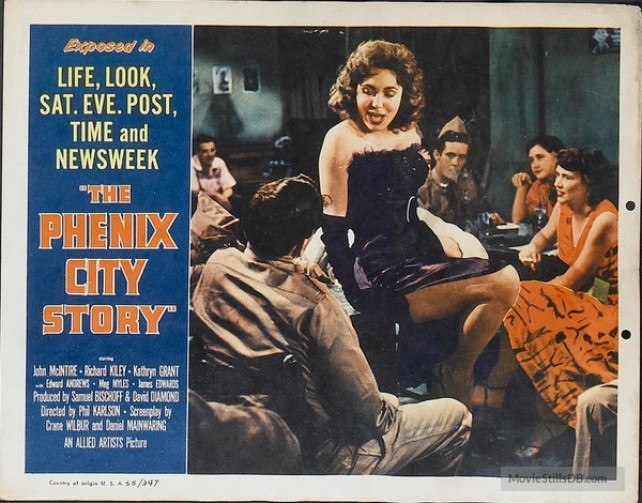

Perhaps Crane Wilbur’s most renown postwar crime film was in 1955 with Allied Artists for the screenplay for The Phenix City Story. Like Canon City, the film depicts real-life events, this time the assassination of political figure Albert L. Patterson, who was appointed to the local council of Phenix City, a small town in the state of Alabama, in an effort to stamp out the rising tide of organised crime in the area. Upon reading about his murder in the newspaper headlines, there was a resulting outcry from the local community and a state of martial law was imposed upon the town.

‘One of the most violent and realistic crime films of the 1950’s, The Phenix City Story pulses with the bracing energy of actual life captured on the screen in it’s establishing shots and key scenes, and punctuates that background with explosively filmed action scenes…’

-Bruce Eder

The film was directed by the underrated Phil Karlson, who made a string of other fantastic noir films around this period, including Kansas City Confidential (1952), 99 River Street (1953) and Hell’s Island (1955). Much of Wilbur’s creative style of storytelling is once again at play here, with a 13-minute newsreel introduction, including actual interviews of people either directly or indirectly involved with the case.

‘My life hasn’t been a path of roses, nor always the straight and narrow road. It has been mostly uphill, rocky climbing, with many a slip and stumble, a few falls and several scars to tell the tale…’

-Crane Wilbur

What a life! Incredibly inspiring and educational.