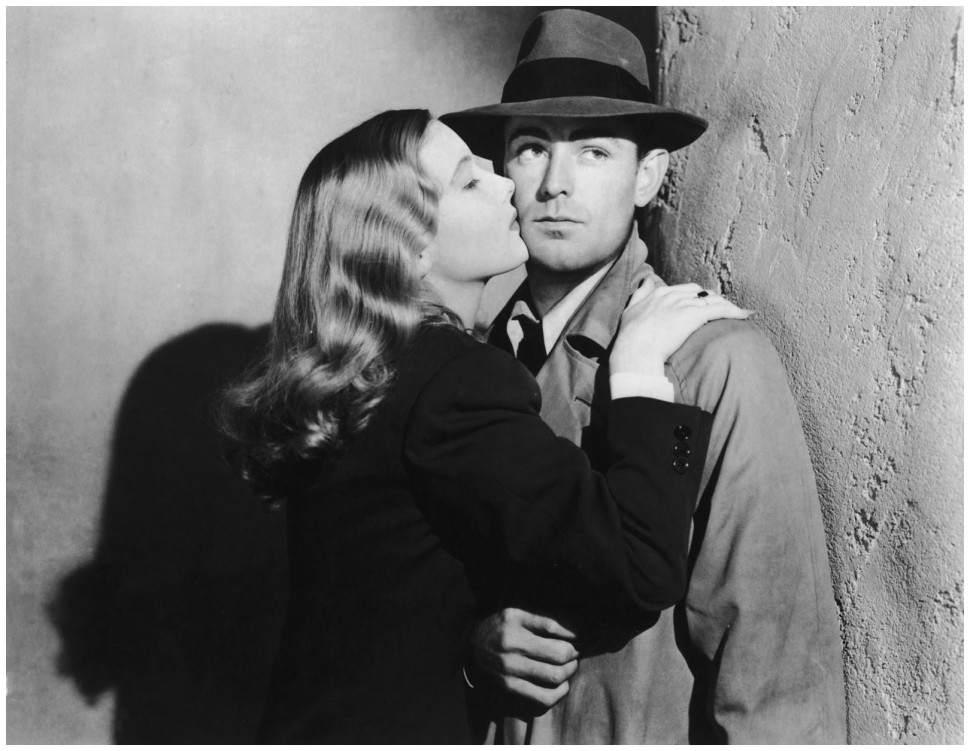

Romanticism, endearment, affection, warmth, sentiment…

When one thinks of a kiss, it’s usually with nostalgic fondness that these tender connotations spring to our minds.

In the fatalistic and cynical world of noir on the other hand, a kiss can mean deception, disenchantment, disillusionment… even death. With it’s heroes cornered into nihilistic predicaments, the claustrophobic atmosphere within it’s dwellings is matched only by it’s brooding visual style on screen.

Widely considered the heyday of noir, Hollywood of the 1940’s had made significant shifts in it’s subject matter and thematic form. Studio executives were soon noting it’s audience’s growing penchant for stories of crime, corruption, blackmail and murder. And soon enough they were snapping up the screen rights to a plethora of stories from pulp novelists and writers like Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane.

And with the steady diaspora of European filmmakers emigrating to the United States following the rise of Fascism and the Second World War, so too were they inadvertently forging nuances in cinema style that came to be affectionately known to cinephiles as film noir.

This March, Privilege of Legends is revisiting a half-dozen of these stark noir films.

Disdainfully smashing all of our romantic preconceptions, and relishing in our unhinged disorientation, these films have accompanied the kiss with sinister juxtaposition and shadowy undertones.

Kiss of Death – 20th Century Fox 1947

Directed by Henry Hathaway, and adapted to the screen from the pen of writing duo Ben Hecht and Charles Lederer, Kiss of Death sees Victor Mature and Richard Widmark (in his first breakout role) as ex-cons and former crime associates; pitted against one another in a fatal game of cat and mouse.

Based on a story by former district attorney Lawrence Blaine, 20th Century Fox attained the rights for the story in November 1946 specifically with Victor Mature in mind to play it’s protagonist.

But Richard Widmark stole the show with his portrayal of heartless goon Tommy Udo, despite the role being initially intended for actor Richard Conte.

Widmark’s nefarious onscreen persona (channeled from his inspiration from reading Batman comics), is still as formidable as ever for it’s callousness and wanton barbarity.

‘From Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death, one will remember that nasty little creep with the wild eyes and high-pitched laugh, neurotic to the core, which Richard Widmark has turned into one of his finest roles…’

‘Panorama du Film Noir Americain’, Raymond Borde & Étienne Chaumeton

With stylish on-location shooting in and around New York City, the towering menace of the city’s imposing walls serve as a claustrophobic backdrop where it’s characters are scurrying through it’s back lanes and alleys.

‘I loved this picture because I liked working outside. It was exciting to manoeuvre things and get work done without people on the streets knowing that you were filming…’

Henry Hathaway

Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye – Warner Brothers 1950

Produced by brothers James and William Cagney under their newly established James Cagney Productions; Jimmy utilised his already reputable name in Hollywood to lure Gordon Douglas over from Columbia Pictures to direct Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye, based upon the novel of the same name by Horace McCoy, author of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

While not quite as notoriously memorable as Cagney’s portrayal of Cody Jarrett (one year prior in Raoul Walsh’s standout noir White Heat), Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye’s escaped jailbird protagonist, Ralph Cotter is amoral to the core; his destructive tendencies spilling like acid onto those unfortunate enough to be within range.

And through no direct association of her own, the beautiful Holiday Carleton (played by tumultuous starlet Barbara Payton), becomes entangled in Cotter’s noxious web, from which her only escape is through the barrel of a loaded gun.

Killer’s Kiss – United Artists 1955

Following the commercial failure of his debut feature Fear and Desire two years before, a young Stanley Kubrick (26 at the time) took the reigns on most creative facets of his second film Killer’s Kiss: producing, directing, storyboarding, editing, and shooting the film himself.

A modest budget of US75,000 was raised almost entirely from the director’s family and friends; the majority of it coming from Bronx pharmacist Morris Bousel (credited as co-producer).

‘Ex-Look photographer Stanley Kubrick turned out Killer’s Kiss on the proverbial shoestring. Kiss was more than a warm-up for Kubrick’s talents, for not only did he co-produce but he directed, photographed and edited the venture from his own screenplay and original story…’

Variety Magazine 1955

The end result was to prove two-fold. Certainly even for Kubrick, having to take on so many productive roles both on set and in the cutting room, the job would have undoubtably been physically and emotionally taxing.

However, because he was, for most part, able to retain creative control on his project (United Artists would eventually recut the film to have a happier ending), Kubrick’s taut noir triangle- involving amateur boxer, club dancer and mobster, bears a visual similitude to the style of cinema that was to make Stanley Kubrick so influential among the next generation of filmmakers… like Martin Scorsese, who cites Killer’s Kiss as a visual influence on his 1980 film Raging Bull (incidentally also featuring a protagonist boxer).

‘Stanley’s a fascinating character. He thinks movies should move, with a minimum of dialogue, and he’s all for sex and sadism…’

Irene Kane

Kiss Me Deadly – United Artists 1955

One reckless gumshoe. A sadistic villain. A handful of neurotically destructive femme fatales. Armageddon in a suitcase…

What more can be said of Robert Aldrich’s reworking of Mickey Spillane’s sixth paranoid pulp novel that hasn’t already been said before? (See the article Hollywood and the Nuclear Age).

With merciless ease, Aldrich’s independently produced firecracker blasts holes through any preconceived notions of plot, character or genre (is it a cold-war era detective story? A science fiction noir?).

Whatever the case may be, few would disagree that Kiss Me Deadly sports the finest onscreen portrayal of Spillane’s hard-headed private investigator, Mike Hammer, played with detonating ferocity by Ralph Meeker.

‘Kiss Me Deadly, disguised as tough-guy detective picture, is actually an anti-nuclear parable with classical allusions- most obviously, to the story of Pandora and her box…’

Alex Cox, The Guardian

A Kiss Before Dying – United Artists 1956

It’s startling how far some people will go to achieve a little power and prosperity.

In A Kiss Before Dying, Gerd Oswald (in his directorial debut) takes burning ambition to murderous depths, transforming the college campus into a callous crime-scene.

Daryl F. Zanuck obtained the screen rights to the 1953 Ira Levin novel after several bids from notable film studios at the time. And his decision to push for the clean-cut Robert Wagner to be cast as sinister prep-school killer Bud Corliss payed off in spades.

‘An early Ira Levin thriller… superbly adapted as an icily acute nightmare…’

Time Out Film Guide

Peeling back the film’s layers; and despite the cumbersome censorship restrictions of Hollywood in the 1950’s (the film’s use of the word ‘pregnant’ ruffled industry feathers at the time, and industry censors forbade the word be mentioned in any advertising or trailers), A Kiss Before Dying still manages to leave it’s audience perturbed by it’s lingering psychology.

The Naked Kiss – Allied Artists Pictures Corporation 1964

With most major film studios in the mid-late 1950’s forced to tighten their purse strings due to the feverish popularity of television, a number of worthy directors began looking beyond the conventional studio system, and turning to independent filmmaking in the latter end of their careers.

For ex-newsroom journalist and former war photographer, Samuel Fuller, this was certainly the case.

And after considerable success with his film Shock Corridor for Allied Artists one year prior, Fuller released another bold and lurid social commentary, that (in typical Sam Fuller fashion), divided it’s audience and invoked rigorous debate.

‘One of the liveliest, most visual-minded and cinematically knowledgable filmmakers now working in the low-budget Hollywood grist mill…’

– Eugene Archer – The New York Times